Collections research

Research is one of the central missions of a museum, according to the recommendations of ICOM (International Council of Museums). In accordance with the code of ethics in force, the Musée d'art et d'histoire de Neuchâtel conducts research on objects in its collections, in close collaboration with university specialists.

Project 2019-2021. The Amez-Droz collection. History of the works and links with the French art market from 1933 to 1945

Between 2019 and 2021 the Musée d'art et d'histoire de Neuchâtel (MahN) conducted extensive research on the provenance of the 69 works bequeathed to the Museum by Yvan and Hélène Amez-Droz. This systematic reconstruction of the chronology of their ownership received funding from the Federal Office of Culture as part of its programme to support research into works of art that were confiscated under the National Socialists.

Since 2016 and pursuant to the Washington Conference Principles of 1998, the Federal Office of Culture (FOC), acting on behalf of the Swiss Confederation which is a signatory to these principles, has provided Swiss museums with financial assistance for their research into the provenance of works in their collections that may have changed hands between 1933 and 1945, and whose chronology of ownership remains unclear. The aim of this research is to identify whether there is any link between the work and the art looted under the National Socialists. In 2018, the MaHN successfully applied to the FOC for a research grant to help fund its renewed investigation into the Yvan and Hélène Amez-Droz collection (Project title: Le Legs Amez-Droz. Historique des œuvres et liens avec le marché de l’art français de 1933 à 1945).

In 1979, the Museum took receipt of the 69 works that had been bequeathed to it by the Neuchâtel-born French art collector Yvan Amez-Droz. At that time, nothing or very little was known about their history. In 2008, a preliminary study confirmed that the works had been acquired in France between 1920 and 1960, and that many of them had links to the complex art market networks in Occupied France, and more broadly to the period when Germany was governed by the National Socialists (1933–1945). In light of this finding, the MahN and its board of directors felt morally and duty bound to conduct further research into the provenance of works in the collection and the circumstances under which the donor had acquired them.

The federal research grant and considerable financial investment by the Museum made it possible to carry out an in-depth investigation using the latest research resources to reconstruct the history of the Amez-Droz collection and identify the circumstances under which the donor had acquired them. The final report was submitted to the FOC, and approved in December 2021. This report and its annexes reflect the current state of our knowledge. It will be reviewed and amended should new information or evidence come to light.

At the national level, this provenance research on the works in the Yvan and Hélène Amez-Droz collection contributes to efforts that seek to investigate the history of works of arts that were gifted or bequeathed to Swiss museums, and acquired by their donors between 1933 and 1945. At the international level, the study contributes to the ongoing and important research on the French art market during the first half of the 20th century.

Our approach complies with the Code of Ethics of both the International Council of Museums (ICOM) and the Association of Swiss Museums (AMS) which requires museums to manage their collections honestly and transparently. It is also in line with the Washington Conference Principles of 1998, which museums have pledged to implement. Last but not least, it honours the memory of the victims of this tragic period in history and fulfils the duty of respect to the donor.

As required by federal rules, the final report and its annexes are available as open access documents on this page.

Final report

Provenance records by work

What is "provenance research"?

Provenance research is a specific field of art history that entails reconstructing the history of a work of art by tracking down its journey from the date when it was created to the present day. There is a particular (but not exclusive) emphasis on works that changed hands between 1933 and 1945, the years corresponding to the period of National Socialism (commonly known as Nazism for short).

What is "looted art"?

"Looted art" is the term that refers to the illegal and forcible plundering of cultural property belonging to individuals or to a group of people/collective body. In the context of National Socialism, it applies more specifically to the systematic seizure of works of art belonging to individuals of the Jewish faith, opponents of the regime and Freemasons in compliance with a confiscation policy instituted by the Nazis between 1933 and 1945, in Hitler's Germany at the outset and then in the countries that were annexed or invaded.

In France, the Vichy government espoused this policy during the Occupation (1940 to 1944) by enacting antisemitic collaborationist laws. The measures resulting from this legislation also included the looting of works of art.

In addition to direct confiscation, new international conventions tend to extend the definition of looted art to include other important aspects such as forced sales, illegitimate and fictitious sales, or sales at knockdown prices.

Looting and the art market in France during the Occupation

In France, the Nazis began to perpetrate wide-scale looting of artistic heritage items belonging to Jewish collectors or gallery owners in the first days of the Occupation, and they continued to do so until the Liberation. In four years, they seized over 60,000 items.

The looted artworks were assembled in Paris, initially in the Louvre and then in the Jeu de Paume Museum, and were subsequently transported en masse to Germany. However, a small number of them – mainly Impressionist or Modernist works – found their way back onto the art market through some of the capital's gallery owners who acted as intermediaries, although no official provision was made for this to take place. This was either because the works had been sold to them by the Germans, or because they were exchanged for items which were more to their liking.

Under the auspices of the collaboration, the Vichy government also introduced a policy of financial dispossession from 1941 onwards, accompanied by a ban on engaging in professions such as gallery ownership, targeted at all Jewish nationals in order to exclude them from economic and social life. The Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs (a Vichyist administrative body) was authorised to administer this measure which included, where appropriate or necessary, the expropriation of artworks that were transferred "legally" by direct sale to private individuals or at public auctions in Paris and the provinces. The profits from these sales were paid directly to the French state.

Although the works offered for sale under these conditions represent only a minor part of the systematic looting to which Jews in France fell victim, they nonetheless sustained the art market in France during the Occupation. The purchasers were private individuals, French or foreign galleries (which, in turn, resold the items) and, less frequently, institutions.

After the war, even though the majority of the property carried off by the Nazis was recovered and returned to its lawful owners by the government that emerged after the Liberation, the works dispersed in the sales often remained untraced. To these should be added the thousands of items returned from Germany whose rightful owners were not found: the number of items that could not be returned to their owners is therefore estimated at more than 10,000.

Some links for further consideration of this subject:

Principles of the 1998 Washington Conference

Vilnius Forum Declaration of 2000

Code of ethics of ICOM and the AMS/VMS

Dans un souci d’intégrer les acquis de la recherche et de stimuler la réflexion face aux enjeux contemporains liés au passé colonial de la Suisse, le MahN entend mettre à disposition du public des sources et des indications bibliographiques sur l’implication de Neuchâtelois dans la traite négrière et l’esclavage.

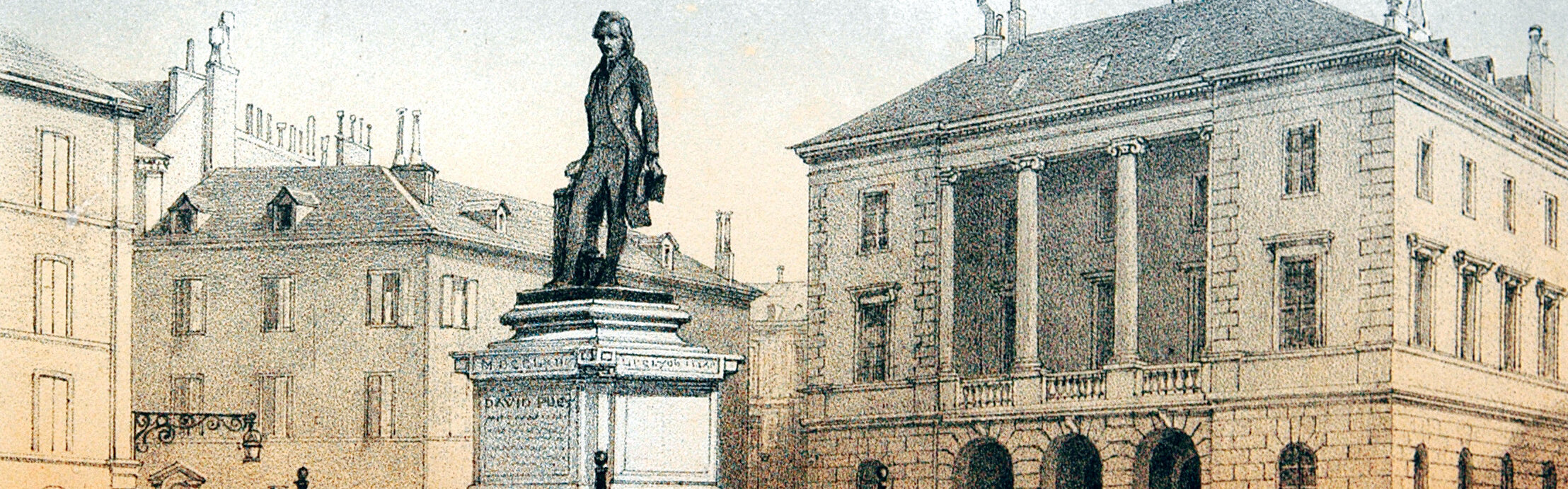

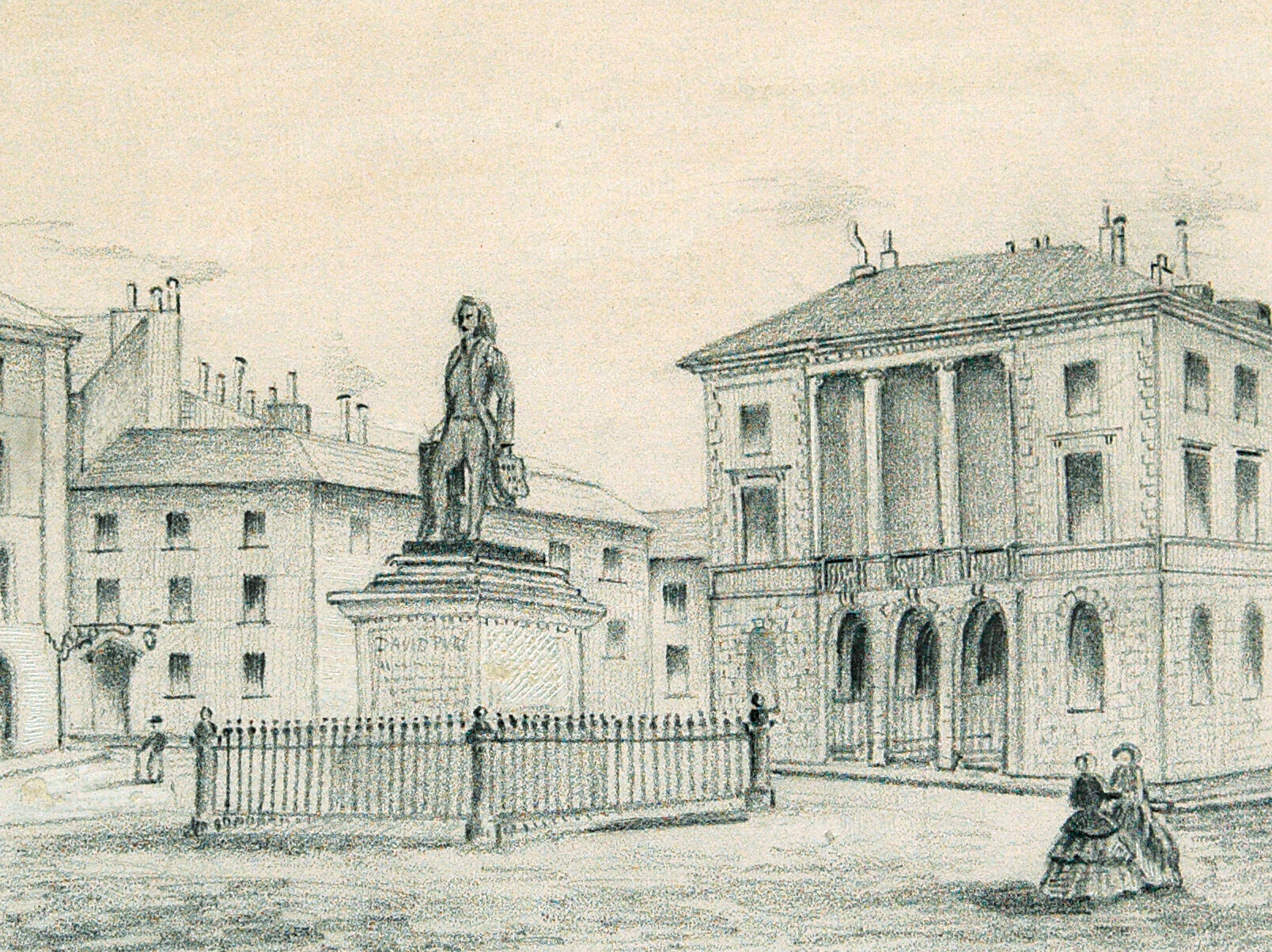

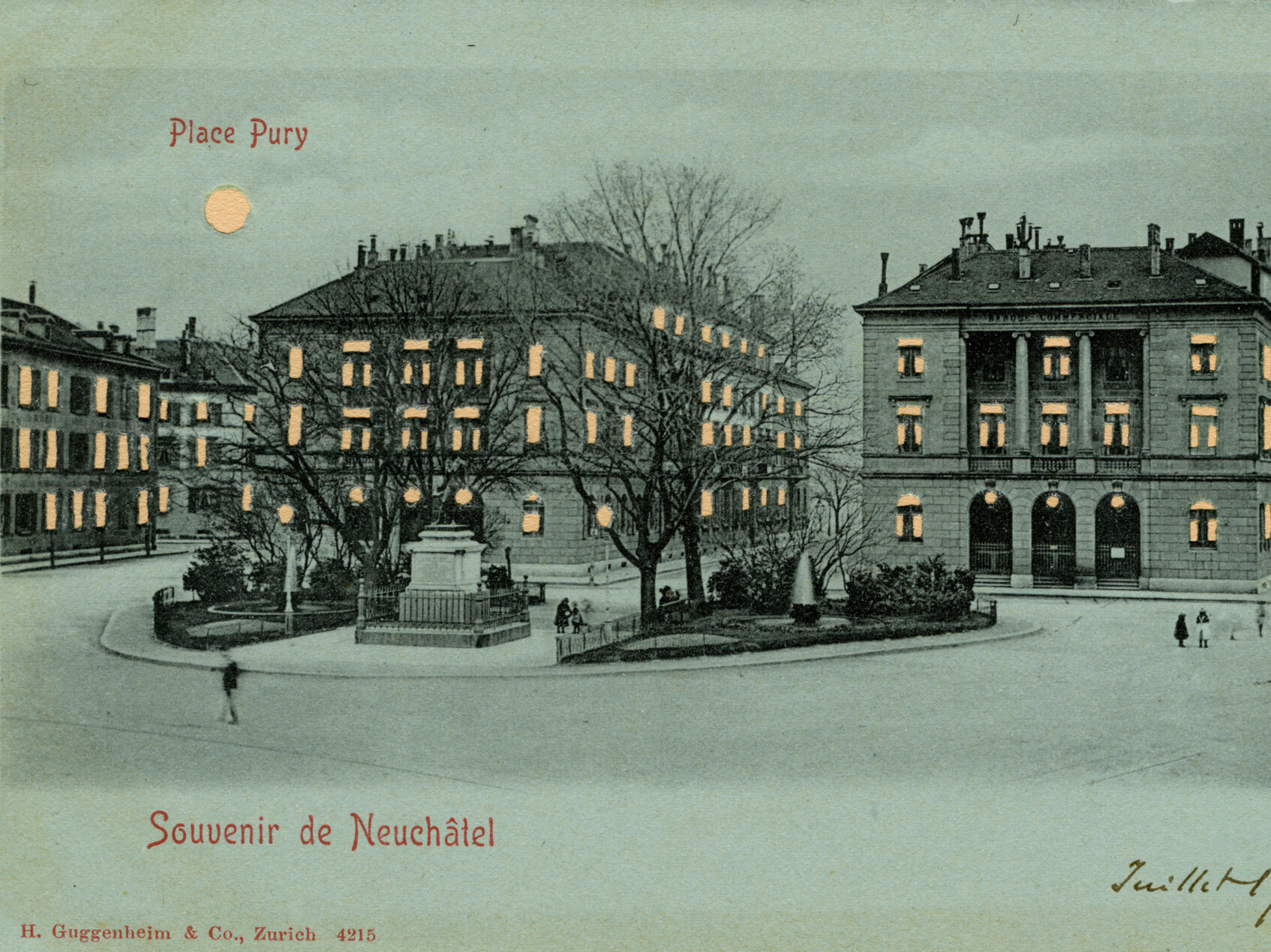

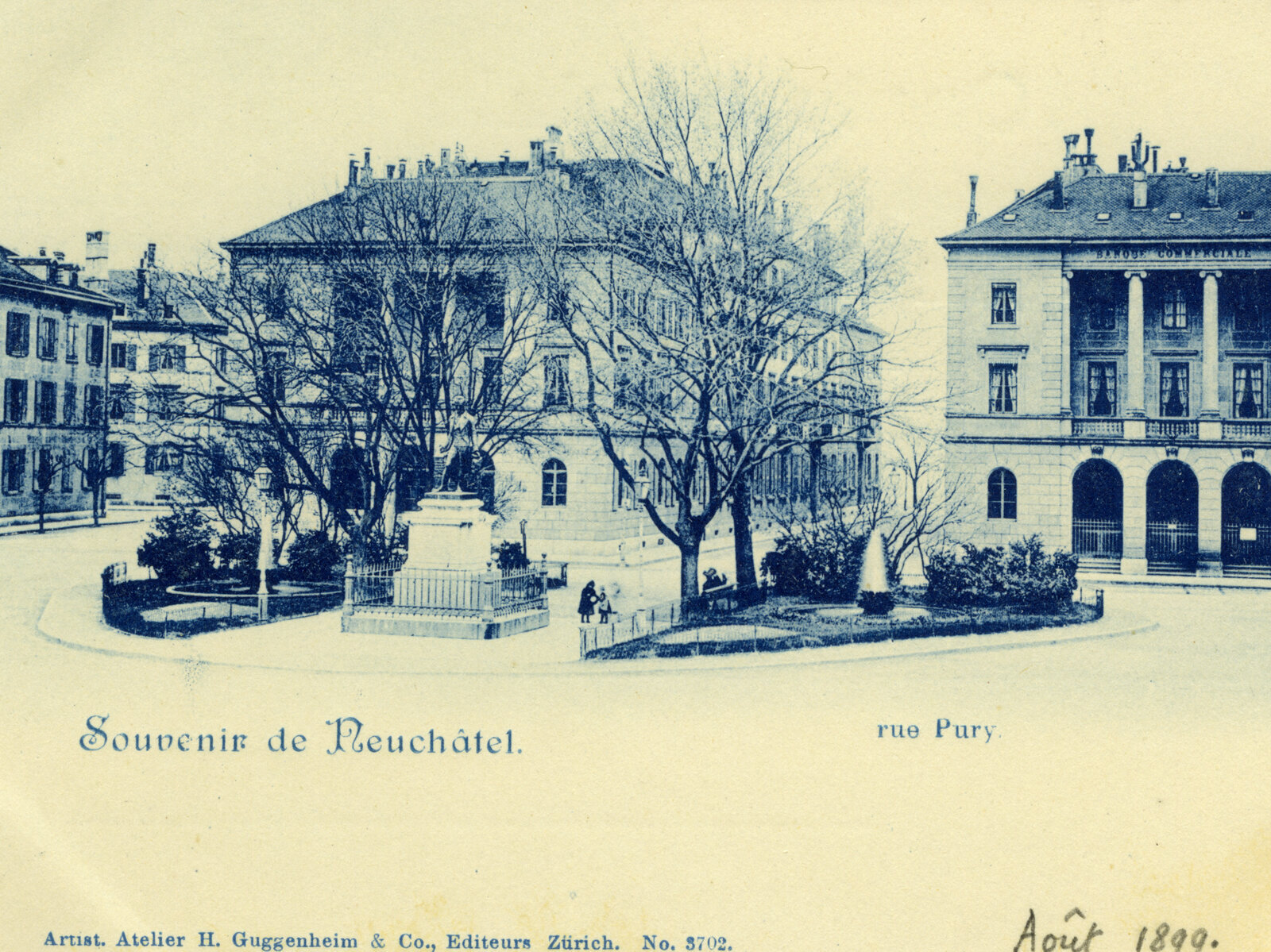

Statue David de Pury à Neuchâtel

- Elisabeth Crettaz-Stürzel et Madeleine Florey, « Une place et une statue », in Passé simple, mensuel romand d’histoire et d’archéologie, 2020/59, pp. 21-22.

- Inès Biscarel, Martin Barretta et Amélie Médebielle, La statue de David de Pury. Soixante ans pour l’élévation d’un monument (1794-1855), travail de Séminaire L’objet comme document, sous la direction de Gianenrico Bernasconi, Géraldine Delley et Régis Bertholon, semestre d’automne 2020, Université de Neuchâtel, 25 p.

- EmmanuelGehrig, « David De Pury, l’embarrassant bienfaiteur », Passé simple : mensuel romand d'histoire et d'archéologie, 2017/29, pp. 19-21.

- Maurice Jeanneret, « L’érection difficile du monument Purry », Musée neuchâtelois, 1955, pp. 97-114, 141-159.

- Carina Pinto Joliat, David de Purry : sur le chemin de la fortune, mémoire de licence sous la direction du prof. Laurent Tissot, Université de Neuchâtel, septembre 2008, 133 p.

Webographie :

- https://penser-un-monument.ch

- https://www.imagesdupatrimoine.ch/notice/article/une-nouvelle-place-pour-accueillir-une-statue.html

Sources - Archives de la Ville de Neuchâtel

- Aubert Parent, Mémoire sur le projet d’un monument, K/II/G.6/7, 1794.

- Finances, fonds Pury, copie du testament de Monsieur David de Pury. E. 222.02.02. 002.

- Manuel du conseil général, n° 36, 1838 - 1847.

- Mémoire sur un projet de monument (Aubert Parent), 1794.

- Plumitif du conseil administratif, 27 avril 1853 - 19 février 1855.

- Plumitif du conseil administratif, 21 février 1855 - 20 avril 1857.

- Travaux publics, Monument, David de Pury, trois boîtes (contenant notamment :

correspondance et pièces diverses, projets d'inscriptions, « projet n° 13, case 3 »).

Sources - Archives d'Etat :

- Fonds AEN MEURON MAXIMILIEN DE -39/04

Bibliographie sélective - Neuchâtel et l’esclavage

- Thomas David, Bouda Etemad et Janick Marina Schaufelbuehl, La Suisse et l’esclavage des Noirs, Lausanne : éditions Antipodes, 2005.

- Bouda Etemad, Investir dans la traite. Les milieux d’affaires suisses et leurs réseaux atlantiques, in Mickaël Augeron et al. (dir.), Les protestants et l'Atlantique, Paris, PUPS/Indes Savantes, 2009, t. 1, pp. 527-532.

- Hans Fässler, Une suisse esclavagiste : voyage dans un pays au-dessus de tout soupçon, Paris : Duboiris, 2007, 286 p.

- Gilles Forster, « Les Suisses et la traite négrière : état des lieux et mises en perspective », Cahiers des Anneaux de la mémoire, 11, 2007, pp. 199-215.

- Gilles Forster, « Pourquoi les manufacturiers suisses dominent le marché français des indiennes de traite ? », in Mickaël Augeron et al. (dir.), Les protestants et l'Atlantique, Paris, PUPS/Indes Savantes, 2009, t. 1, p. 530.

- Gilles Forster, « Neuchâtel, l’esclavage et la traite négrière : entre mémoire refoulée et histoire occultée », in Eternal Tour 2009, Festival artistique & scientifique, Hauterive, éditions Gilles Attinger, 2009, pp. 64-75.

- Gilles Forster, Les indiennes de traite: une contribution neuchâteloise à l'essor de l'économie atlantique, in Elisabeth Crettaz-Stürzel et Chantal Lafontant Vallotton (éd.), Sa Majesté en Suisse : Neuchâtel et ses princes prussiens, éditions Alphil, Neuchâtel, 2013, pp. 270-276.

- Krystel Gualdé « Neuchâtel, Nantes et l’Afrique : une production textile pour la traite Atlantique »in Lisa Laurenti, avec la collaboration de Chantal Lafontant Vallotton et Philippe Lüscher, Made in Neuchâtel. Deux siècles d’indiennes, cat. d’expo, Neuchâtel, Musée d’art et d’histoire, Paris : Somogy, Neuchâtel : Musée d’art et d’histoire, pp. 52-63.

- Aka Kouamé, Les cargaisons de traite nantaises au XVIIIe siècle. Une contribution à l’étude de la traite négrière fançaise, thèse de doctorat de l’Université de Nantes, 2005, pp. 492-508.

- Chantal Lafontant Vallotton, « Une exposition et ses enjeux », in Lisa Laurenti, avec la collaboration de Chantal Lafontant Vallotton et Philippe Lüscher, Made in Neuchâtel. Deux siècles d’indiennes, cat. d’expo, Neuchâtel, Musée d’art et d’histoire, Paris : Somogy, Neuchâtel : Musée d’art et d’histoire, pp. 7-9.

- Olivier Pavillon, Des Suisses au cœur de la traite négrière : de Marseille à l’Île de France, d’Amsterdam aux Guyanes (1770-1840) / Olivier Pavillon ; préface d’Olivier Grenouilleau ; postface de Gilbert Coutaz, Lausanne: Éditions Antipodes, 2017, 159 p.

MahN août 2021

1777 Par testament, David de Pury lègue la quasi-totalité de sa fortune à la bourgeoisie de Neuchâtel.

1786 Décès de David de Pury à Lisbonne.

1794 Les autorités de la Ville de Neuchâtel envisagent de rendre un hommage à David de Pury. Des premiers projets sont développés. Ils seront tous abandonnés.

1805 Un buste à l'effigie de David de Pury est installé dans le Péristyle de l'Hôtel de Ville où il se trouve aujourd'hui encore.

1826 La Ville relance l'idée d'un monument public. Aucune suite n'est cependant donnée au projet.

1844 Un nouveau projet prévoit d'ériger une statue sur une place à la rue du Seyon qui vient d'être créée. Une souscription publique permet de réunir une somme importante.

1848 La statue est réalisée par David d'Angers, sculpteur parisien renommé.

1848 Au lendemain de la Révolution républicaine, des tensions portant entre autres sur l'emplacement de la statue divisent l'ancienne Commission du monument et les nouvelles autorités.

1849 La statue est fondue à Paris, sous la surveillance du sculpteur David d'Angers, puis transportée à Neuchâtel.

1852-1855 Des controverses sur l'emplacement de la statue opposent les nouvelles autorités au Comité de souscription, composé d'adeptes de l'Ancien régime.

1855 Après révocation du Comité de souscription, la statue, érigée sur un piédestal, est inaugurée le 6 juillet par les autorités en place.

MahN, août 2021

Neuchâtel fait la lumière sur son passé

En été 2020, suite à un épisode de violence policière contre un Afro-américain, une vague de protestations touche le monde entier, faisant vaciller des monuments historiques liés à l’entreprise coloniale et à l'esclavagisme. C'est le cas aussi à Neuchâtel, où deux pétitions exigent, l'une le retrait, l'autre le maintien de la statue de David de Pury. La Ville de Neuchâtel, par ses autorités exécutives et législatives, a présenté un an plus tard un rapport adopté à l'unanimité. Celui-ci présente des mesures à court, moyen et long terme pour mieux assumer le passé et rendre l'espace public plus inclusif.

Après la pose d'une plaque explicative et l'installation d'une oeuvre d'art à proximité de la statue de David de Pury, la Ville a lancé, le 23 mars 2023, un parcours interactif, "Neuchâtel empreintes coloniales", emmenant le public dans l'histoire de Neuchâtel sous l'angle de l'esclavage et du colonialisme. Cette balade gratuite, réalisée avec l'application totemi, restitue ces réalités du passé grâce aux vestiges du patrimoine bâti.

Parcours: Neuchâtel, empreintes coloniales

Article du DHS (Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse) sur David de Pury

Par ailleurs, le DHS a publié également en 2024 de nouvelles versions actualisées des articles sur la famille de Meuron, sur Charles-Daniel de Meuron et Pierre-Frédéric de Meuron, ainsi qu’un article inédit portant sur Auguste-Frédéric de Meuron.